After Roche returned to Resolute from Pim’s Investigator rescue mission, Kellett began strength training the men while carpenter Dean completed the finishing touches on the captain’s sledge, HM Sledge Erin. (All of the sledges had names, flags and mottos.) Kellett had the men haul gravel on their sledges to the ships. Not only did this increase their strength but, with the new ballast in the holds, it also prepared the ships for sailing later in the summer.

Additionally, Kellett distributed extra travelling clothes to the men. Roche recorded some thoughts about his in an unpublished journal:

“For a short party of twenty or thirty days, the spare drawers, flannel shirt, one pair of stockings, one pair of wrappers, towel and soap, may be dispensed with…I never wore myself a single particle of cloth whilst traveling, a suit of chamois leather answered the purpose of keeping out the wind and was not near so heavy….In the severest cold two pair of woollen drawers and one pair of duck overalls are quite sufficient…In the warm months one pair of drawers and the chamois drawers will be ample. In lieu of the thick flannel waistcoat a thin chamois leather waistcoat worn outside two thick flannels with or without a shirt, over which in cold weather [one can add] a duck overall jumper. On the feet one pair stockings, one pair blanket wrappers, boot hose and moccasins soled with leather [were] the usual ‘rig’ of the travellers. With these I used to wear a pair of sealskin boots (hair inside) soled with leather. I found these very comfortable. They seldom required cleaning inside. and I never had cold feet with them.”

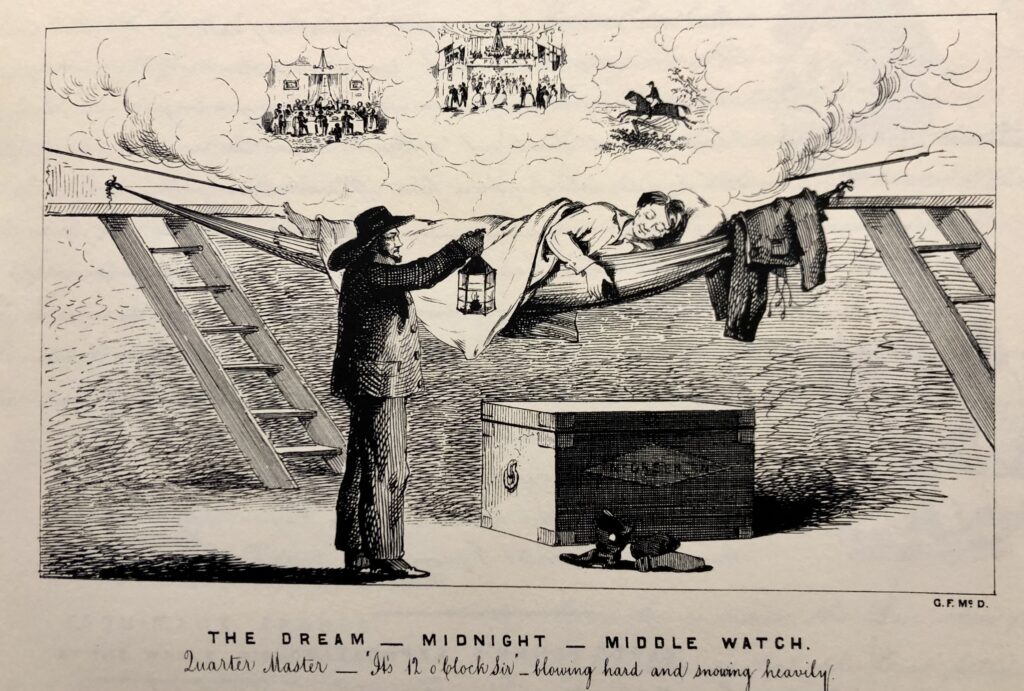

He did not have cold feet, but I would hazzard a guess that very few of his shipmates got within a few feet of him if they could help it! In their shared tents they may have fallen asleep quickly to avoid the results of Roche’s cut-back wardrobe.

Continued tomorrow!

Word Press seems to have lost my last update, so I am redoing it here Sunday 7 March 2021, from my manuscript:

On the morning of departure day, 4 April, Kellett raised a flag on Dealy Island’s summit, then the officers joined him for a large breakfast. Afterward everyone assembled on the ice. The sledges, arranged in divisions, pointed toward their directions of travel. With flags fluttered in the breeze Kellett gave a rousing speech, followed by enthusiastic cheering. He wasn’t an overly religious man but after the cheering died down he offered a prayer.

McClintock and De Bray led the largest team, headed NW for Hecla and Griper Bay. McClintock’s Star of the North, carried a smaller satellite sledge. McClintock’s men were: Captain of Sledge George Green, Ice Quartermaster; Henry Giddy, Bo’s’u’n’s Mate; John Salmon, Fo’c’sle Captain; Royal Marine Privates John Hiccles and Jeremiah Shaw; Richard Kitson, John Drew (replacing Thomas Hood) and Richard Warne, Able Bodied Seamen.

McClintock’s orders from Kellett were to carefully examine the NW coasts…

‘…for traces of the missing, and depositing records in conspicuous places for the combined purpose of a search for traces of Sir John Franklin, and of depositing notices in conspicuous places as to where supplies are left (for any parties that might reach such positions from Captain Collinson’s [ships]…you will keep ample notes, or remarks on the new coast you will have to travel along, a journal of your proceedings, and obtain data for putting on paper the coast or islands you may discover. To assist the memory in protracting your walking journey (and future navigators), you will name on your skeleton chart all capes, bays, islets, &c, if possible, from something characteristic of themselves. On the same chart you should lay off daily the true course you have been steering, and the estimated distance you have marched, leaving for your return the correction of this dead reckoning by the astronomical observations you may be enabled to obtain, and without sacrificing to them time might be occupied in marching.

Possessing as you do the same opinion with myself, that yours is a most important direction for search, I feel confident that your personal exertions will be equal to the importance of your mission, and that those under your command will vie with each other in seconding you.

It now only remains for me to assure you of the deep interest I feel for your own personal welfare and success, as well as of those under your command.‘

De Bray had the sledge Hero and eight men: Captain of the Sledge John Cleverly, Gunner’s Mate; James Miles, Leading Stoker; Samuel Deane, Carpenter’s Mate; Alexander Johnstone, Steward; William Walker, Stoker; Robert Ganniclift and Thomas Hartnell, Able Bodied Seamen.

In De Bray’s orders Kellett indicated his high regard for McClintock, an active officer…‘…whose example you will do well to follow… and I feel assured that from the zeal you have manifested in the equipment of your sledge as well as in the other matters connected with traveling, you will do great credit to the distinguished service to which you belong.’

Kellett accompanied McClintock for seven days, with Erin, and Richard Hobbs, William Johnson, Frederick Brooke, William Kluth, James Cornelius, Thomas St. Croix and John Halloran to create a cairn of supplies…

Hamilton headed to NE Melville Island, then he would circle round to Hecla and Griper Bay, with George Murray, Ice Quartermaster; William Colwill, Blacksmith; Royal Marine David Ross, Abraham Surry, Cooper. Joseph Bacon, cook, and Able-Bodied Seamen John Coglin and Thomas Wilson on the sledge Hope. So few men remained the departing men could hardly hear their enthusiastic cheers. Mecham and Nares, heading due west, had the advantage of a favourable easterly wind and raised their sails. The other teams had to struggle without help from the wind gods. As a result, after traveling nine hours, McClintock’s team only covered 10 ½ miles. By the evening the weather improved, but rough terrain, ‘cheerless and forbidding in the extreme…’ dashed their high hopes the next morning. When a northerly wind worked itself into a full gale on the 6TH, it caused the temperatures to drop to -10°F, blowing right into their faces and the snow reduced their visibility to only 20 – 30 yards. The men struggled to erect their tents in deep snow drifts. They remained in them for four days, where -11°F and cramped conditions meant…

‘...our sleeping bags and furs [were] very wet, the snow-drift having penetrated from without, and the condensed vapour from our provisions, our breath, and the evaporation from our bodies, from within.‘

The gale ended on the 11TH allowing the men to spread their bags and furs in the bright sunshine. When they broke camp they found the snow had filled the deep ravines making their work much more difficult and dangerous. But the intrepid explorers carried on and eventually reached their autumn cairns. These men navigated hummocks and ravines, battling thick fog and raging snow storms while the rugged terrain chewed up their wooden sledges, keeping the carpenters busy. To augment their diet they hunted muskox and reindeer, hares and ptarmigan, which boosted both their strength and morale.

On 11 April Kellett and his men returned to camp, where the remaining Resolutes and Intrepids had spring cleaned and repaired both ships. Although Kellett had set his shoulder to many an arduous task over the past 30 years, he admitted sledge hauling was the most difficult labour he’d ever undertaken. Working along side his men had given him greater sympathy for them, and valuable insight into the effort required. Seeing his willingness to pitch in increased the men’s regard for Kellett too.

McClintock and Hamilton parted ways on 13 April. McClintock and De Bray continued heading NW and Hamilton, after depositing provisions, turned back south. Hoisting sails had its own dangers…”

9 March 2021 Blog Post: 1853 spring sledging continued, from my manuscript (italicised passages are quotes within my ms):

“Sometimes the wind was too strong: one day a sledge turned turtle three times. When McClintock reached the Camp Nias Cairn the provisions, thankfully, were still in good condition. McClintock took apart Captain Parry’s nearby 1822 monument to check for any recent records. Finding none he left the usual notices, and then headed toward Cape Fisher. Once again a gale forced them to make camp, though this time for only one day. The 17TH was calm and they continued towards the cape, making good time until two days later when their sledges started falling apart.

Out of 68 rivets in my sledge, 32 were found broken and 14 rivets were broken in the Hero, in fact, all the rivets in the dead flat of both sledges are gone, but near the extremes where there is little or no spring in the runner they are as firm as ever.

McClintock and De Bray reached Cape Fisher on 19 April at midday. The ice there was much easier to traverse. They saw a herd of 15-16 muskox, but all the wily beasts escaped. The following day they had better luck and McClintock shot a bull. His two female companions remained with him, resolutely facing the men. In order to carry away the dead ox the Intrepids had to chuck stones at them to drive them off.

As the days lengthened, and the bright sunshine began melting the snow, the danger of snow blindness grew. McClintock would soon have to begin night traveling. Passing Grassy Cape, the men made good progress sledging on the easy and level shore ice. They reached the most northwesterly point of Melville Island on the 30TH at Sandy Point, after which the coast lead off to the SW. Sadly, Thomas Hood’s health began deteriorating: he had severe pain in his side and began spitting blood. On 1 May McClintock made the difficult decision to send Hood back to Resolute, and the following day De Bray and several others departed with him on Hero. En route Stoker John Coombs, having been in perfect health, suddenly sank to the ground and was dead before anyone could reach him. De Bray wrapped his body in canvas and continued east, arriving at Resolute midday on 18 May.

Meanwhile McClintock continued south. By 5 May he was just north of Terrace Cape where he sent Star of the North to search Ibbett Bay. Then, taking six days’ supplies with his small satellite sledge, and Giddy and Drew, McClintock headed south into much rougher terrain, hoping to cross paths with Mecham. The small sledge allowed him more manoeuvrability as he headed toward Cape Terrace. From the top of a hill on the following day McClintock named the bay below him Purchase Bay, for Intrepid’s senior engineer. Continuing south McClintock built another cairn on a conspicuous spot, leaving a message for Mecham. Then, finding no traces of any missing men, his team headed north again and on the 8TH camped near Ibbett Bay. Crossing it McClintock met the rest of his men led by Green on Star of the North, who reported finding no Franklin or Collinson traces anywhere around the bay. The men feasted on McClintock’s fresh muskox in such quantity that, had they been back home they…

…couldn’t eat half so much…as they can here, and even if they could, they would be ashamed to do so.

The reunited team travelled toward Cape De Bray, reaching their depot on the 11TH at 03:15. After resupplying, they headed across the strait toward unexplored land. Their heavily laden sledges and newly fallen snow made headway extremely difficult. When McClintock checked the weight on Star of the North he found, to his horror, each man was hauling 65 pounds over the 215 pound limit. He helped unload half the gear, took the sledge four miles ahead, where they offloaded the rest. Returning to the provisions left behind, they reloaded and brought them forward. Continuing this time consuming process they gradually made their way across the strait hauling manageable weight…

11 March 2021 Spring Sledging 1853 continued:

The men hauling their sledges used up a great deal of fuel. From the Arctic Blue Books we can see an example of what the men were eating:

“We now consume a kettle full of stewed venison for supper, and ⅔ of a pound of pemican each for breakfast, besides a pint of chocolate; we also have ¾ pound of bacon for luncheon, and ¾ pound of biscuit daily. The kettle is capable of holding 13 pints of water, and is always crammed full of meat for supper, yet, this we consider a ‘light meal’ when divided amongst the nine of us. If we had the fuel to cook with, we wouldn’t restrict ourselves, now the fresh meat is abundant; and I think still more liberal allowance than we enjoy at present would be beneficial to the men.“

By mid May McClintock was exploring along the coast of Prince Patrick Island, and some smaller islands along its northern shore. From my ms:

“When [McClintock] arrived at Resolute and Intrepid on 18 July [he and his men had] been away an unprecedented 105 days, covering 1,408 miles averaging 10½ miles daily, of which 768 miles were new territory. McClintock didn’t, however, connect with Mecham or Nares, who were completing their own extraordinary journeys.”

First Lieutenant George Mecham had the sedge Discovery, and was away for 91 days, from 4 April to 6 July. Born in 1828 in Cove, County Cork Mecham was an Irishman like Kellett . His men were James Tullett, Bo’s’un’s Mate; John Weatherall, A.B.; Charles Nisbett, A.B.; James Butler, A.B.; William Manson, A.B.; William Humphries, Private Royal Marine; Samuel Rogers, Private Royal Marine. Discovery carried 40 days’ provisions and 100 days’ equipment, and Kellett’s orders for Mecham were to complete:

…the most persevering and extended search along the SW coast of Melville Island for our missing countrymen, or traces…you will take command of HM Sledge Discovery, manned with seven men, and…Perseverance also manned with seven men…[and] will proceed to Winter harbour, and from thence across the land to Lidden Gulf, following the coast of Melville Island westerly as far as practicable, returning to this ship without fail by 15th of July…You and Commander McClintock are both marching west…[and if you meet with] time and provisions left…you will consult with him, and do what you think best for the advancement of the object of our mission…Yourself being a veteran in Arctic traveling, and also some under your command, I have great expectations from your journey; I feel confident that you will attempt anything for the good of the service you are about to be employed on.

12 March 2021 Blog Post:

Kellett always made his men feel valuable members of the team. His orders to Nares, who was young and inexperienced, are a perfect example of Kellett’s leadership style:

[From my manuscript] George Nares was in charge of Perseverance. His men wereThomas Joy, Ice Quartermaster; Thomas West, Captain of the Main Top; George Kelly, Captain of the Fore Top; James Le Patsurel, Captain of the Hold; William Griffiths, A.B.; William Bailey, Private Royal Marine. Perseverance was out 58 days, until 1 June. Nares completed a detailed survey of Cape Bounty and environs on his return, brought back the game he’d hunted en route. Kellett’s orders included morale boosting words:

‘Lieutenant Mecham…in the autumn, spoke so highly of your exertion, zeal, and care of your party…[I am] confident that you will ably and efficiently second him in this very important line of search.‘

What follows is another example of Kellett’s ability to manage his men. His way filtered down through the ranks, as his officers tended to treat the men in their charges in similar ways:

[from my manuscript] If the parties crossed paths Kellett didn’t place Mecham under the command of the superior officer, instead he trusted Mecham and McClintock to reach agreement together on a way forward. Departing on 4 April and heading SW, and steering for Cape Bounty, Mecham and Nares searched the entire south coast of Melville Island, thick with bays and inlets. They then crossed the same strait as McClintock had, to explore the southern area of the newly named Prince Patrick Island. The deep snow made for heavy traveling, and unlike the parties heading due west, Mecham’s team couldn’t use their sails this first day. That afternoon James Butler fell from the hauling ropes to collapse in exhaustion. However, like a true Brit, he revived after a rest and a cup of tea. On the second day they raised their sails. After making camp, Mecham issued grog all round to celebrate William Humphries’ 21 years of naval service.